We hear a lot about “attracting and retaining talent” as a way to sustain the economic growth Minnesota has experienced since the end of the Great Recession. The private sector has been oriented toward the goal of talent retention for some time; the public and nonprofit sectors also know well that developing, keeping, and attracting skilled people are central to the future well-being of Minnesota. Attracting smart, hard-working innovators to the state — and keeping the ones we already have — will become more important than ever in the decades to come.

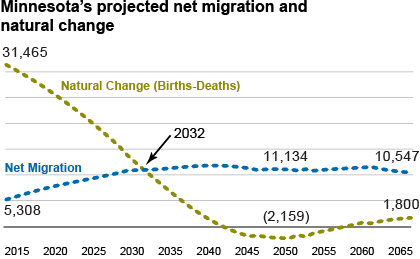

We are entering a new era, where migration’s influence on our total population will rise. According to our projections, by the early 2040s, if our state is to experience any population growth at all, it will necessarily be from migration (as deaths will then outnumber births).

Over the next 15 to 20 years, the baby boomer generation will continue to exit the labor force, causing labor force growth to slow nearly to a halt. Thus, Minnesota will experience a heightened need for migration in order for the state to grow at all, but especially to shore up its labor force needs.

Our office recently analyzed patterns of migration to better understand who is moving to Minnesota and who is moving away. Though the Census Bureau doesn’t ask people directly about their reasons for moving, the social and demographic characteristics of movers can give us some clues. We know that people are on the move for many reasons — they change addresses for job prospects or educational institutions, to reunite with family or friends, or to seek out amenities they desire.

Here are a few of our key findings:

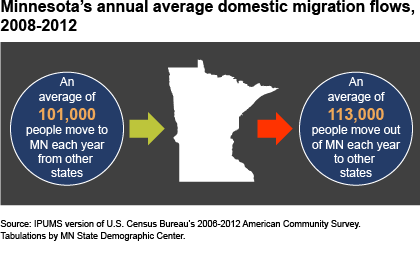

- Minnesota is now losing residents to other states: Between 1991 and 2001, Minnesota’s domestic (state-to-state) net migration was consistently positive. However, each year following 2001, Minnesota has lost more people to other U.S. states than it has gained. Recent estimates put domestic losses at approximately 7,000 to 12,000 people per year.

- We are gaining even more residents from immigration: Despite these domestic losses, even greater numbers of arriving international residents — including foreign students and work VISA holders, refugees, and other immigrants — have resulted in sustained positive overall migration. They are reflected in our state’s growing foreign-born population.

- Young adults are on the move: The likelihood of moving, both in and out of Minnesota, peaks in the late teens and early 20s, and then tapers gradually into older adulthood. However, net losses to domestic migration are seen among three segments of Minnesotans: age 18-24 (about 9,300 lost annually), age 35-39 (about 1,500 lost annually), and age 60-69 (about 2,200 lost annually).

- Many students come here for college – but even more leave: While 21,000 young adults move to Minnesota each year to attend college or graduate school, even greater numbers of students (29,000) leave the state each year. In fact, two-thirds of Minnesota’s total annual domestic net loss is due to Minnesota students leaving for higher education, and far fewer return in the post-college years. Thus, retaining more of our college-bound young adults at in-state institutions may be a key strategy to long-term population retention and labor force development.

- Race and ethnicity are not a big factor in leaving: Of those leaving Minnesota for other states, the share by race and ethnicity closely approximates the distribution in Minnesota’s general population, with the exceptions that non-Hispanic whites are slightly less likely to leave than we might expect (given their share of the general population), while non-Hispanic Asians are slightly more likely to leave than we might expect. Other groups are leaving the state roughly proportionally.

Compared to other Midwestern states (excepting oil-rich outlier North Dakota), Minnesota competes favorably in terms of overall positive net migration. But considering the reversal of domestic migration to a net outflow more than a decade ago, and given our state’s near-term labor force challenges with the boomers’ retirement, additional attention to our migration situation is warranted.

More than 100,000 people come to Minnesota from other states each year, and an even greater number leave Minnesota for other states.

These sizeable flows of people present an opportunity to change the migration equation to better benefit our state. Minnesota should work to stem and reverse domestic losses, redouble efforts to attract and integrate new residents, especially young adults, and seek to retain its current resident population.

Positive migration is key to fueling our economy and maintaining a high quality of living in Minnesota in the years to come.

Read the full report: Minnesota on the Move: Migration Patterns & Implications, from which these findings are excerpted.

Susan Brower is the Minnesota State Demographer and directs the Minnesota State Demographic Center. She travels the state talking with Minnesotans about the new social and economic realities that are brought about by recent demographic shifts. Susan’s work applies an understanding of demographic trends to changes in a range of areas including the state’s economy and workforce, education, health, immigration and rural population changes. Follow the Demographic Center on Twitter.

Related Insight articles:

Minnesota's aging population: Prepare for lift off

6 surprising trends about Minnesota’s millennials

Hiring difficulties: Skills gap or more complex?

Immigration in Minnesota: 5 things you should know

Opinions expressed in Minnesota Compass guest columns do not necessarily reflect the views of Minnesota Compass. Compass welcomes a range of views about issues pertaining to quality of life in Minnesota.