by Jacob Wascalus

In November, the proposed Southwest Light Rail line (LRT) took a step closer to reality after the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) approved a major source of funding for the project. The LRT, which is expected to begin operation in 2023, will span 14.5 miles and connect Eden Prairie, a suburb southwest of Minneapolis, to Target Field, in downtown Minneapolis. The line will have 16 stops in total and will connect with multiple bus routes and another light rail line.

At a cost of $2 billion, the LRT has drawn a lot of speculation on its possible benefits. How will it affect access to jobs? What influence will it have on the built environment? Will traffic congestion improve? Below we take a look at some possible outcomes.

More jobs within reach for public transit riders

According to the Metropolitan Council, which is overseeing the project, approximately 35,800 people lived within a half-mile of the proposed suburban stations in 2014; in downtown, they calculated that 16,400 residents had access to the five stations the Southwest LRT will share with the existing light rail line. By 2035, the Met Council anticipates both of those numbers to balloon: 55,800 residents living within a half-mile of the suburban stations and 35,600 living downtown.

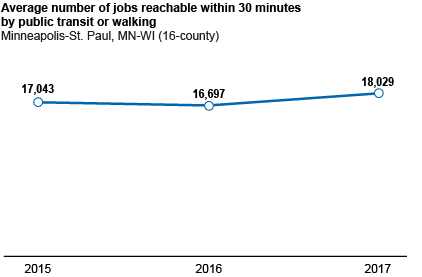

Metrowide, about 18 percent of workers take public transportation, walk, bike, work at home, or otherwise don't commute via an automobile. Compared to the rest of the country, the Twin Cities region fares pretty well among large metropolitan areas for access to jobs via public transportation, ranking 11th. In 2020, the average commuter taking some combination of bus, light rail, and walking could access nearly 19,000 jobs within 30 minutes. That's up slightly from 2017, which was just over 18,000 jobs.

How many more jobs will be added to that figure when the new Southwest LRT opens in four years?

"We would expect to see greater gains in access," says Brendan Murphy, lead researcher at Accessibility Observatory, noting the limited transit options currently operating in the southwestern suburbs. "We're bringing more census blocks into the fold, into the shed that you can easily get to a transit line from. So I would expect to see some pretty sizable bumps."

Murphy went on to explain that the 18,029 figure is actually a bit misleading. Because the Accessibility Observatory is comparing cities to each other, they determined the average number of jobs accessible via public transportation across the core base statistical area—a large geography that includes 16 counties and where, in some places, there are limited jobs and public transit.

"You'll see a lot more marked differences if you look at only those areas that are serviced by transit," he said.

Case in point: According to the Metropolitan Council, there were roughly 64,300 jobs within a half-mile of the suburban Southwest LRT stations in 2014 and 126,800 in downtown Minneapolis.

Spending an entire work week sitting in a car

In 2013, the average driver commuting to work in the Twin Cities spent an extra 46 hours sitting in rush hour traffic. In 2014, the trend worsened. Drivers lost 47 hours a year stopping, starting, and plodding along in rush hour traffic. By 2023, the excess time spent in traffic may be greater than 2014's numbers, but for many of the tens of thousands of people who live near the Southwest LRT line, the option to ride the train will be a viable way to avoid this time-wasting inefficiency.

Tim Lomax, a Regent's Fellow at Texas A&M's Transportation Institute who was part of the team that calculated the amount of time commuters spent sitting in traffic, noted that some commuters will opt for a ride on public transportation, particularly a train, because they appreciate the reliability.

"Even if it takes them 20 minutes to drive and 30 minutes to ride, that 30 minutes is much less stressful, and they can do something else while they're riding," he said.

Lomax went on to explain that congestion numbers won't necessarily drop because of a single infrastructure investment like the Southwest LRT. Instead, he points to the potential of a rail line to spur economic development and land use changes along its route.

"What we've seen successful rail lines do is create opportunities to redevelop an area," he says, noting that reducing congestion typically requires multiple transportation and land use changes. "They can spur more density, more mixed-use development: Jobs, shops, homes, all in the same walkable neighborhoods. [For nearby residents,] it creates trips that are relatively close, within walking distance."

Helping address a skills and spatial mismatch

Newly created and existing jobs along the LRT route, especially ones in the service and retail industries, will be attractive employment destinations for some people in the region.

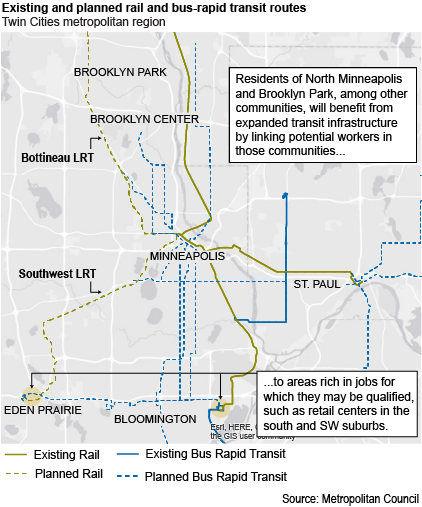

A recent study conducted by the University of Minnesota highlights the challenges residents of some disadvantaged communities, particularly ones with higher levels of unemployment, face in reaching jobs for which their skills would make them suitable. According to Spatial and Skills Mismatch of Unemployment and Job Vacancies, North Minneapolis and Brooklyn Park, among other communities, will benefit from expanded transit lines by linking potential workers in those communities to areas rich in jobs for which they may be qualified, such as retail centers in the south and southwestern suburbs. The Southwest LRT will provide a critical link in this transportation network.

Currently, from North Minneapolis and the northern suburbs, job-rich areas in the south and southwestern suburbs are accessible by automobile and less-frequent bus service. For many, this rules out those locations as potential employment destinations. The Southwest LRT, along with the proposed Bottineau Light Rail line, which will traverse the western border of North Minneapolis up to Brooklyn Park and will connect with the Southwest LRT, will expand the employment shed for many residents in this area. The various proposed bus-rapid transit lines will also further this expansion.

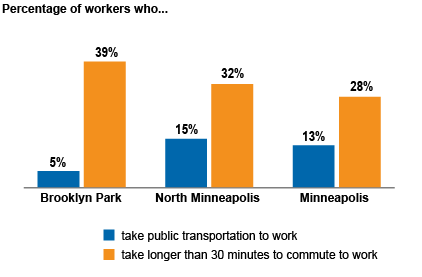

Just 5 percent of commuters in Brooklyn Park take public transportation to work, compared to 11 percent of workers in North Minneapolis and 10 percent in Minneapolis. But where 29 percent of commuters take longer than 30 minutes to travel to work in all of Minneapolis, it takes 34 percent of commuters in North Minneapolis and 35 percent of commuters in Brooklyn Park longer than 30 minutes to get to work.

That's a lot of people traveling a long time to get to work. With the Metropolitan Council estimating that employment opportunities along the Southwest LRT corridor will increase significantly by 2035—80,900 jobs within a half-mile of the proposed suburban stations and 145,300 in downtown—the additional transit options will help reduce the time burden for many residents of this area and will open up additional areas of potential employment.

What's next?

The ink is still drying on the financing agreement that the FTA just signed, but it's never too soon to speculate on the local and regional ramifications of a large transportation investment. While the full effect that the Southwest LRT will have on the region isn't fully known, several outcomes are likely: increased access to jobs for commuters who take public transportation, additional transportation options for people who live near the proposed route, and expanded areas of potential employment to disadvantaged communities, including communities north of downtown Minneapolis and in the northern suburbs. After its first few years of operation, with more data available, further analysis will shed light on the impact that the $2 billion investment has had on the people, places, and jobs of the Twin Cities metropolitan region.

Want to dig deeper?

The transportation topic area of Minnesota Compass has data and trends on access to destinations, congestion, pavement condition, and transportation expenses. Our geographic profiles contain information on vehicles per household, methods of transportation to work, and travel time to work for Minnesota's regions, counties, and cities of 1,000 people or more.

The Accessibility Observatory is a program of the Center for Transportation Studies at the University of Minnesota, focused on the research and application of accessibility-based transportation system evaluation. Accessibility, which examines both land use and transportation systems, measures how many destinations, such as jobs, can be reached in a given time.

The Texas A&M Transportation Institute is a transportation research organization that focuses on developing and maintaining safe and efficient transportation that saves lives, time, and resources.