by Jacob Wascalus

For the majority of Minnesotans, access to a vehicle is almost a necessity. Whether commuting to work, going to the supermarket, or running an errand, many people require the use of an automobile to move from one place to another. This is especially true of the 45 percent of people who live in greater Minnesota.

But what happens when you don’t have a car in greater Minnesota? We took a look at two populations in greater Minnesota whose lack of a vehicle could make them vulnerable: working-age adults who are unemployed and older adults who are living alone. How prevalent are these populations? And what options do they have for overcoming mobility obstacles?

Unemployed and living in poverty

More than 17,000 working-age adults (aged 24 to 64) in greater Minnesota do not have a car and are unemployed or not in the labor force. While this population makes up a little more than one percent of the 24 to 64 year old cohort in greater Minnesota, roughly 70 percent of this population, or about 12,000 individuals, earn less than the federal poverty threshold. Without a dependable means of transportation, these residents may experience challenges in finding and maintaining employment, getting to medical appointments, or accessing food.

One option that may be available to them is public transportation. According to the Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT), 44 public transit systems operate across greater Minnesota, ranging from fixed-route bus lines in more urbanized areas to demand-response (“Dial-a-Ride”) operations in rural areas. These systems are quite popular. In 2015, the entire network of transit operators recorded approximately 12 million boardings, a record high. And it’s no surprise why: these systems fill a vital role for their users, connecting them to essential destinations, such as employers, retail and grocery outlets. Yet despite their popularity, most residents of greater Minnesota move from place to place without the help of public transit. According to 2013-2017 estimates from the American Community Survey, 88 percent of workers aged 16 and older commuted to work by car, truck, or van.

For carless residents who secure a job, purchasing an automobile can be challenging. To take out a loan to buy a car, banks typically require proof of income sufficient enough to make note payments as well as a credit score high enough to reflect a recent history of paying back debts. If a person has been unemployed, chances are he or she might not meet these thresholds.

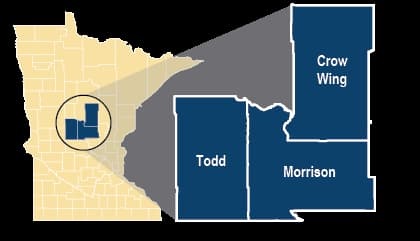

“You need to get to work,” says Roxanne Hurt, a community services specialist at the Tri-County Community Action Partnership (TCCAP), which operates a car-loan program in Crow Wing, Todd, and Morrison counties. “You need to get to the doctor and to the grocery store, but sometimes people get on hard times.”

Approximately five percent of the households in TCCAP’s service area have no vehicle. That works out to about 2,900 households. While that is a small share of the overall population, of the residents who have jobs, 88 percent commute by a car, truck, or van. And it’s no wonder why: 62 percent of workers travel more than 10 miles to work. A few transit “dial-a-ride” services operate in the area, but with limited hours and geographic reach, public transit isn’t always a viable option for some carless adults.

TCCAP operates its car-loan program for low-income residents of Todd, Crow Wing, and Morrison counties.

To help address this problem, TCCAP targets its car-loan program to low-income individuals who are not able to purchase an automobile with traditional financing, such as through a bank. Their loans are capped at $4,000, with payback terms that cannot exceed two years. Although the organization makes only 12 or so loans a year, the program has room to grow. And the benefits of taking out a loan with TCCAP go beyond just help with buying a car. Because the organization reports payments to credit agencies, the program also helps repair borrowers’ credit.

“This is more for people who are working to get back on their feet,” Hurt says.

Older adults living alone

Isolation and food insecurity are two potential vulnerabilities faced by older adults (65+) who live alone and do not own a car. This is especially true in rural areas, where population is sparse and where the distance to retail and grocery destinations can be far.

In greater Minnesota, nearly 24,000 older adults live alone and do not have a car. While some of these residents may have family and friends to help them move from place to place, and others may rely on public transit or other modal means, how do carless older adults who have neither a strong family or social network nor convenient public transit options access food purchasing destinations, medical facilities, and social engagements?

According to Michele Ver Ploeg, an economist at the United States Department of Agriculture, older adults who do not have vehicles and live far from grocery stores have a heightened risk for food insecurity. Her observation is based on survey data related to health and retirement for people older than 55.

“Among the elderly, those who lived in a food desert were no more likely to say that they were food insufficient,” she explained. “But when we looked at those who lived in a food desert and didn't have a car, they were more likely to say that they were food insufficient. There’s a sizable difference.”

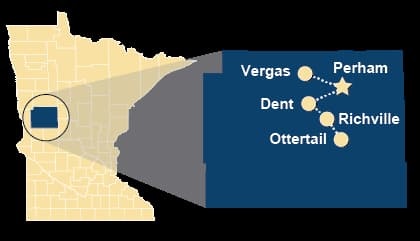

One organization looking to address this hardship is the Bridge Community Pantry. Bridge operates a mobile market that serves parts of west central Minnesota, circulating monthly and inviting those in need, including older adults, to pick up food for free. The organization started as a food shelf, with a fixed location in Perham, Minnesota. But after learning that many people in their geographic service area couldn’t access the market, both because of transportation issues or operating hours, the organization decided to launch its mobile market to bring food relief to four different communities in their region.

Based in Perham, Bridge Community Pantry delivers food to four communities each month.

From January 2019 through October 2019, more than 100 households made 410 visits to the mobile market. Twenty-four of those households are older adults who live alone.

“We help people who need an occasional helping hand,” says John Leikness, the Bridge Community Pantry’s executive director, explaining that use of the mobile market has increased every year since its inception in 2007. “But the truth is we wish no one needed our services.”

Who should carry the burden?

With population projections showing a large growth in the number of people aged 65 and older in greater Minnesota through 2030, the ranks of carless older adults living alone is likely to grow. How will they access necessary destinations and avoid social isolation? For working-age adults who are both carless and struggle to find a job, what will happen when our current healthy job market sours? Organizations like TCCAP and the Bridge Community Pantry help address the needs of these two vulnerable populations, but given their limited resources and geographic reach, they can help only so much.

This begs a much larger question: Is it fair to ask charitable and non-profit organizations to fulfill the needs of vulnerable populations? What role should the public sector play? For instance, what role do policymakers have in investing in infrastructure that could help to broaden employment opportunities, such as increased broadband? Access to high-speed internet, after all, is the first step in creating more telecommuting opportunities—jobs where access to a vehicle isn’t necessary.

Or how can planners direct retail and housing development to co-locate in more centralized areas? Perhaps those older adults who live alone and don’t have a car could relocate to areas where driving isn’t necessary and where isolation is easily avoided.

We’re interested in knowing how communities across Minnesota are addressing these issues. What creative solutions are you implementing to connect vulnerable populations to the resources they need? Write to info@mncompass.org to tell us about the policies and actions that your community is taking to help vulnerable populations living in your areas.

For more information about the organizations featured in this article and for an interactive map that displays the location of food deserts, see the links below.

Tri-County Community Action Partnership

Note on Carless Data

The estimates of carless individuals in greater Minnesota are based on Minnesota Compass analysis of microdata from the 2013-2017 American Community Survey. These data are available from the IPUMS USA database: Steven Ruggles, Sarah Flood, Ronald Goeken, Josiah Grover, Erin Meyer, Jose Pacas and Matthew Sobek. IPUMS USA: Version 9.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2019.https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V9.0